1.

First, a memory: First light peeking behind the curtains, the last guest gone, you reaching under the sink, rummaging through old bottles, hopeful for a couple more fingers of gin. For the road. Us sharing in the dregs and soon enough, you, slamming a fist on the table, tears in your voice.

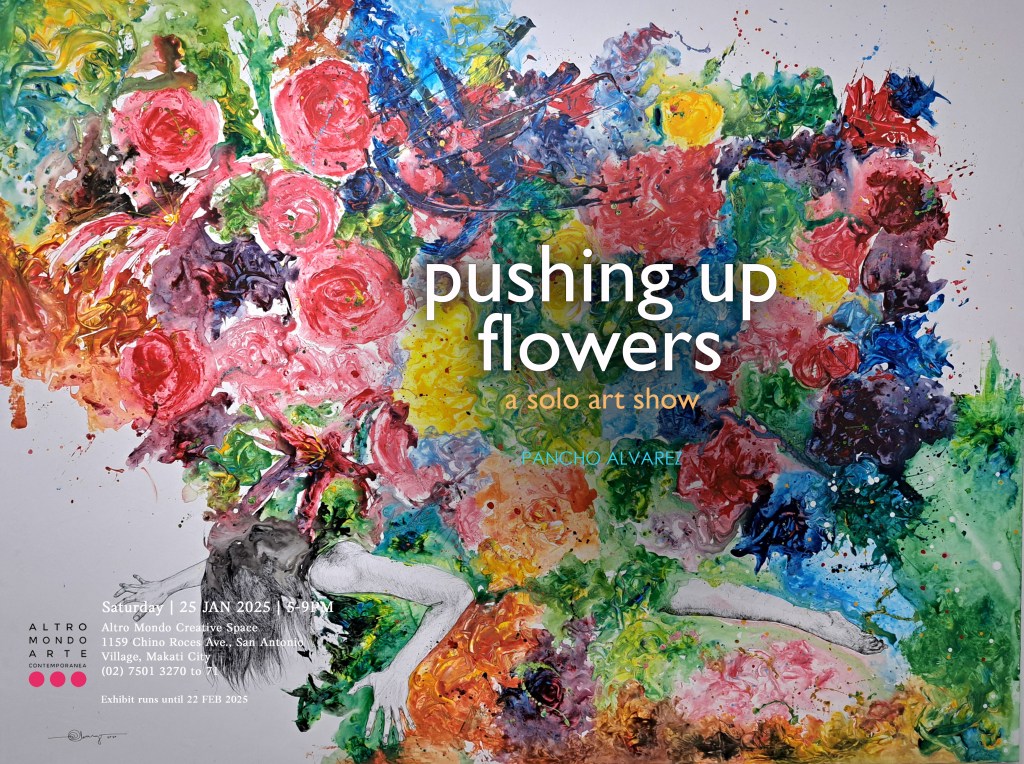

Which is to say: There is tenderness in Pushing Up Flowers, and there is violence too.

2.

I read your accompanying essay with interest. I know much of the narrative– the toxic ex-girlfriend, enamored with blades; the collapse of old friendships; the subsequent self-exile to Naga; the fascination with storms; your mother’s sickness; the amorphous, often dreadful, unnameable thing always hiding beyond the horizon.

Examining the paintings in your collection, staring at them for long minutes, then looking away, walking away as I hold them in my mind, returning for another look, I ask myself: Do I see these in them? I am not sure I do.

I know, however, that these things did happen, and so I see them for what they are: As context, a coagulation of scenes and situations, an entire universe (amorphous, often dreadful, unnameable) that the canvas can barely keep at bay. They exist in the flick of the wrist, the burst of force. “Largely intuitive,” you said when asked how you chose the colors, the directions of the splotches, the jaggednesses. Meaning, through impulse and mystery, rage and regret, gentle afterthought, memory blurred by sentiment.

But then again, I see, too, Tita Lays– clutching at her abdomen, or straining to get up. I see her hands en route to a face concealed by a thick shock of hair, the pain both assumption and foregone conclusion. I see the fine point of the pen, the negative spaces, each flowing strand, each whorl on weatherbeaten skin.

I see the flowers, and I see Tita Lays not so much pushing them up but keeping them upright, allowing them structure, allowing them form, not so much wild soil but a vase– the subject of thoughtfulness, molded and set down on a furnace and delicately held, almost always on the verge of shattering. An encasement less violent, less mortal than the blooms they contain. I remember the poet Eric Gamalinda and his words: “Just like the perfect seasons/ they will die/ and I will die/ and you will die also;/ no one knows who will go first,/ and this is the source/ of all my grief.”

This is, perhaps, a tension we are all called to endure. We are called to endure many things, as you know.

3.

I wonder, sometimes, about the fact that our friendship has, without doubt, enjoyed a surplus of laughter, despite all that we have had to endure. Is it artifice? Are we averse to intensity, afraid to dig into our chests and lay our hearts bare? Is it fear? I hope not.

Here is what I believe: That there are seeds within us that threaten, all the time, to rage into color, and we should count ourselves fortunate if, at some point, we are able to find our own encasements, our own ways of remaining taut without snapping, of keeping upright as we make sense of our own mortality and of the world.

Perhaps this is what is sometimes called beauty. Perhaps this is what is called art.

Mikael de Lara Co

Poet and Palanca Awards Hall of Famer